Chapter Eleven, Credit Clearing, the “UnMoney”

If there were no money, any system of crediting sellers and debiting buyers would be fully competent to accomplish the work now performed by money. – Hugo Bilgram, 1914

In Chapter 10 we explained that the highest stage in the evolution of reciprocal exchange is “credit clearing,” and that banks have been using it for the past few hundred years to settle obligations amongst themselves.[1] In this chapter we will further describe the history and applications of credit clearing, and we will show how clearing can be used to offset claims among not only groups of banks, but also among any persons or entities that have financial claims against one another. Most significantly, it is a process that may be applied among buyers and sellers of goods and services to directly offset their respective claims without involving banks as middle-men and without the need for conventional bank- or government-created currencies.

Direct Clearing Among Buyers and Sellers

Credit clearing is actually an ancient process. During the Middle Ages, credit played a major role in the various European “market towns” which hosted, at regular intervals, trading fairs in which merchants from widely scattered areas would gather to trade their goods. It is reasonable to conclude that the process of credit clearing would have been fundamental in their trading activities. This is evidenced by the fact that these market towns typically provided market courts for settling disputes under “merchant law” that was separate from common law and could be adjudicated in a matter of hours or days. James Davis points out that, “At the pettiest level of sales credit, many traders appear to have acted both as creditors and debtors, and there is evidence for running accounts, reciprocal dealings and a ‘complex of claims and counterclaims,’” and that, “Credit oiled the wheels of trade, and market courts dealt in small-scale sales debts that were integral to local retail and wholesale commerce. A market court ostensibly lowered transaction costs and thus attracted more traders by aiding a perception of the market as ‘fair, affordable, efficient’”.[2]

The possibilities of direct credit clearing among buyers and sellers have long been recognized. In modern times, as early as 1914, Hugo Bilgram and L. E. Levy noted that, “If there were no money, any system of crediting sellers and debiting buyers would be fully competent to accomplish the work now performed by money.”[3] They further suggested that:

“Were a number of businessmen to combine for the purpose of organizing a system of exchange, effective among themselves, they could clearly demonstrate how simple the money system can really be made. The greater the number of businessmen that would thus cooperate, the more complete would be their own emancipation from the obstruction to commerce and industry which existing currency laws impose.”[4]

They then went on to propose such a system and describe how it might operate, which I summarized in one of my previous books[5] and in a website post.[6] I’ll not repeat that here because the context today is much different from what it was in 1914, but we will present a similar proposal based on what has since been learned and tailored to our current realities. I believe that it is no exaggeration to say that the creation and operation of such credit clearing systems is crucial to reversing the present trend toward economic ruin and global tyranny and changing the course toward realizing our human potential and the emergence of a peaceful, convivial civilization in which all can thrive.

Buying and Selling on Credit

It is common practice among business firms to buy and sell on “open account,” which means that if you are a buyer, the seller trusts you to pay sometime later for the goods or services you’ve received. This is like you running a tab at your favorite restaurant or bar, which means the proprietor trusts you to pay when you are ready to leave. In the case of business transactions, however, the period between the delivery of goods or services and the expected payment date is typically a matter of weeks or months instead of minutes or hours. Consider a typical small enterprise, let’s call it the Alpha Company, which does business on “open account” with a group of both customers and suppliers. That means it extends credit to customers and receives credit from suppliers. When Alpha Company makes a sale, it has money coming to it. In accounting terms, a sale gives rise to what accountants call an “account receivable” (A/R). Similarly, when Alpha Company makes a purchase, it owes money to someone else. In accounting terms, a purchase gives rise to an “account payable” (A/P).

Clearing through Banks Versus Mutual Credit Clearing

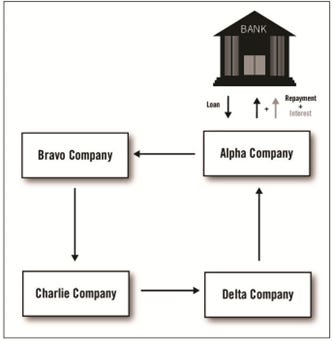

Now consider a hypothetical case with two possibilities. First consider the use of conventional money and banking to clear accounts among a group of companies that trade with one another, then compare that with clearing accounts independently and directly within a mutual credit clearing circle. Figure 11.1 depicts the conventional payment process using bank credit money that has been borrowed into circulation, while Figure 11.2 shows the direct clearing process that requires no bank credit. Suppose that Alpha owes Bravo $100, Bravo owes Charlie $100, Charlie owes Delta $100, and Delta owes Alpha $100. In the conventional process, one or more of the companies must borrow money from a bank in order for them to pay what they owe to each other. In the simplest scenario (Figure 11.1), Alpha borrows $100 from the bank to pay Bravo, who then uses that money to pay Charlie, who then uses it to pay Delta, who then uses it to pay Alpha. Everyone has now been paid—including Alpha, which can now repay the $100 it “borrowed” from the bank. But in addition to the $100 principal, Alpha must also pay the bank some amount of interest. In sum, each company used a third-party credit instrument, the money that the bank created and deposited to Alpha’s account, to pay the others what was owed. But interest must be paid for the use of this bank-authorized credit money. Herein lies the greatest flaw in the debt-money system. When the bank made the loan, it created the principal amount but not the amount of the interest. In order for Alpha to pay back the principal, plus the interest, it must compete in the market to capture enough money to pay the interest. If it succeeds, there will be a deficiency of money in some other similar circuit. As we showed in Chapter 6, there is never enough money in circulation at any given time for all borrowers to pay what they owe to the banks. This makes the centralized debt-money system like a game of “musical chairs” in which there must be some losers.

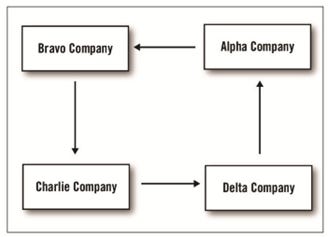

But these companies can pay one another using their own credit without the involvement of a bank, which is portrayed in Figure 11.2. As in the previous scenario, each owes an amount to another. But now, suppose Bravo is willing to accept Alpha’s self-issued credit instrument (IOU) in payment, and each of the other companies in turn is also willing to accept Alpha’s IOU. Alpha Company writes an IOU and uses it to pay Bravo, Bravo then passes Alpha’s IOU on to Charlie in payment for what it owes, then Charlie passes it on to Delta to pay its debt, and Delta finally returns Alpha’s IOU to Alpha in payment for its debt. Now all debts have been paid, no money was borrowed, and no interest needed to be paid.

In practice, there is no need for anyone to literally write an IOU because the companies simply agree to buy and sell among themselves without using conventional money and to settle their accounts using the clearing process. They simply keep a ledger in which each company’s purchases from one company are offset by making sales to another company. Each company’s account is allowed to be negative to some extent for some period of time. This is a credit clearing circle in which all the participants agree to give each other a pre-arranged line of credit, which is typically, and should be, interest-free. This is an organized way of extending the usual business practice of selling on “open account” from a bilateral agreement to a multilateral agreement (i.e., rather than selling on credit to individual customers, it sells on credit to a group of customers).

Direct Credit Clearing Makes Conventional Money and Banking Obsolete

The ultimate step in reciprocal exchange, then, is the direct clearing of purchases against sales. Goods and services pay for other goods and services, so money, as we’ve known it, becomes obsolete. Direct credit clearing among buyers and sellers obviates the need to use any third-party currency or credit instrument, such as bank credit or government fiat currency, as a payment medium. Direct credit clearing is the “gunpowder” that makes the “castle” defenses of conventional money and banking obsolete and useless. Just as the adoption of checks allowed banks to circumvent the legal limitations imposed on the issuance of banknotes, so does the adoption of mutual credit clearing circles allow traders to free themselves from the limitations imposed by the monopoly of bank-credit and government-created money.

With the proper implementation strategies and the application of sound financial principles, direct mutual credit clearing is an unstoppable technological advance that has the power to ameliorate myriad economic, political, and social problems and establish a solid foundation needed to enable civilization to make a major leap toward a harmonious, sustainable, and dignified way of life for everyone.

The necessary steps in achieving that transformation are to:

Organize mutual credit clearing exchanges that transcend the privileged creation of conventional checkable bank deposit money and the monetization of government debts,

Network those clearing circles together into a worldwide payment system based upon a web of trust, and eventually,

Define and utilize an independent, nonpolitical, concrete standard of value and unit of account that cannot be manipulated to the advantage of any particular bank, cartel, government, group, or individual.

Various approaches to achieving that program will be described in subsequent chapters, but let us first summarize the benefits of direct credit clearing:

• Within any trading community, there need never be any shortage of credit or currency to enable all legitimate trades to occur.

• Credit allocation is determined on a democratic and decentralized basis by the participants themselves according to their own values, objectives, rules, and levels of trust in one another.

• Participants can avoid the exploitative interest costs and fees imposed by banks.

• Participants can avoid the adverse effects of outside factors like the inflation of political currencies, restrictive credit policies of banks, and global economic and financial instabilities.

Mutual Credit Clearing Systems as Clearing Houses for Buyers and Sellers

The Bilgram and Levy plan was conceived at a time when the gold standard was still operational and paper currency was still redeemable for gold, but their basic ideas and structure provide a useful point of departure for present day innovators and reformers. However, I would not advise the implementation of the B and L proposal as it was originally presented, because they encumber their credit clearing system with much unnecessary and self-defeating “baggage,” which I described when I posted it on my website.[7]

I have long maintained that “The creation of sound exchange media (money/currency) requires that it be spent into circulation by trusted producers of real valuable goods and services that are in the market and available to be delivered in the near-term. Money or currency, then, is a mere place holder for real economic value; it is a credible promise that will be accepted as a form of payment.”[8] The same holds true for the credit that is allocated to participants within a credit clearing circle, since such credit serves as an internal currency. I agree with E. C. Riegel that debit balances are already “backed” by the goods and services that they represent and the issuer’s promise to deliver them, so no additional backing is needed. He says:

“Money's [currency’s] material backing is that which the seller surrenders in exchange for it; its moral backing is the buyer's promise to back it with an equivalent value when in turn he becomes the seller. Further than this, money has no backing and more than this it does not need, but this is indispensable.” [9]

There is also no good reason for a credit clearing exchange to accept deposits of official fiat money except in the event of the withdrawal of a participant who leaves with a debit balance. It is, for instance, the usual practice of present-day commercial trade exchanges to have on file a credit card number for each member, charging that card only for service fees that are levied in cash and for the amount of any debit balance remaining when that member leaves the system. Members wishing to leave who have a positive balance are not allowed to convert their trade credits to cash but must instead spend them within the system prior to leaving. There is also no need to redeem trade credits for fiat money.

Since all participants benefit from the clearing process, the cost of operating the system should be borne equally by all, so there should be no interest charges applied to negative balances. If fees are based on account balances, they ought to be applied equally to both negative and positive balances. But rather than applying interest levies on accounts, I’ve proposed a revenue model based on the principle that one should pay fees in proportion to the amount of service they receive, which in this case is the amount of value cleared for an account, i.e., a small fee on each transaction, paid by both the buyer and the seller. Remember, if no one ever had a negative balance there would be no credit and nothing to clear. Credit is what makes the business of exchange go round.

Such are the conditions that would enable real independence from the dysfunctional and exploitative political fiat money regime.

In a traditional clearing process, each member has some amount of tangible resources that are used to settle account deficits. Obviously, a long string of deficits would soon deplete one’s resources. The settlement feature provides a check on any member’s ability to draw excessively from the system. If a mutual credit or LETS system has no provision for settlement, what is there to prevent a member from continually buying more than they sell and becoming a chronic debtor? There must obviously be some limit on the debit balance that a member is allowed to carry. The questions of how those maximum debit balances should be determined and what their amounts should be are of primary importance in the design and operation of a credit clearing system and will be discussed shortly.

Direct Credit Clearing—An Illustrative Example

The fact is that goods and services pay for other goods and services, whether or not we use some form of money as an intermediate payment medium. Ultimately, it is your sales that pay for your purchases. Direct credit clearing makes unnecessary the use of any third-party credit instrument. We can think of the “trade credits” within a mutual credit clearing circle as being our own internal currency that we create and control. Of course, we still need a measure of value or pricing unit to quantify the amounts of our internal credit claims and obligations. As a matter of convenience, we may use the dollar as a measure of value, but there is no need to use Federal Reserve notes or bank-created deposits or any other political currency as the payment medium.

A credit clearing association is based on an arrangement in which a group of traders, each of whom is both a buyer and a seller, agree to allocate to one another sufficient credit to facilitate their transactions among one another. The rest is merely bookkeeping. In such a system, the total amount of credit outstanding at any point in time can be thought of as the money supply within the system. That amount is determined by adding up the sum of either the positive balances (total claims) or the negative balances (total obligations). These two sums, of course, are merely two ways of looking at the same quantity—the total amount of credit that members have allocated to one another. As such, they must always be equal to one another.

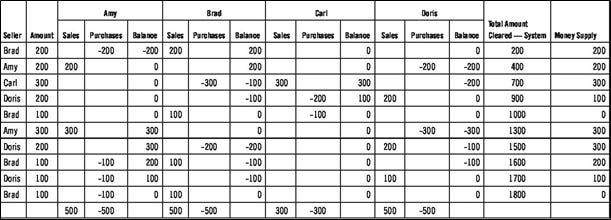

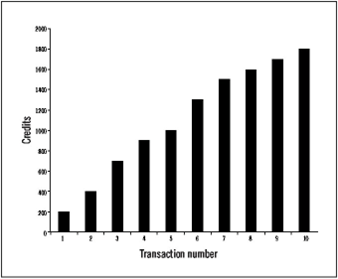

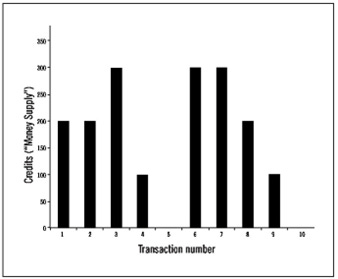

To show how direct credit clearing between buyers and sellers works, it will be helpful to examine an example involving a small set of transactions among only a few participants. It should be carefully examined. Table 11.1 shows ten hypothetical transactions among four participating traders. As each transaction is processed and posted to the ledger, the second to last column shows the cumulative amount cleared, which is shown graphically in Figure 11.3. The final column shows total amount of credits outstanding at each point in time, which can be thought of as the internal “money supply.” This is shown graphically in Figure 11.4.

It can be seen from Figure 11.4 that the “money supply” need not be an ever-increasing number, as it is in the political money system. Note how the money supply fluctuates up and down, increasing as participants draw upon their prearranged credit lines to make purchases, and decreasing as existing credit balances are spent, at which point those credits no longer exist. Clearly, the quantity of money in a credit clearing system is self-adjusting in accordance with the trading needs of the associated members and does not play the same role as in a commodity money system where the money supply is relatively inflexible, nor in the political debt-money system in which credit is centrally controlled and much of the money is created by fiat on an improper basis.

The fact is that present-day banking is itself mainly a credit clearing process in which additions and subtractions are made to the bank customers’ account balances, but banks also perpetuate the myth that money is a “thing” to be lent. If a client’s balance is allowed to be negative (by means of an overdraft privilege), the bank considers that to be a “loan” and will charge interest on it. Has the bank loaned anything? No, what the bank has done is to allocate some of our own collective credit to the “borrower,” and for this they claim the right to charge interest.

It is clear from the example just discussed that any group of traders can organize to allocate their own collective credit among themselves—according to their own criteria and interest-free. Such systems can avoid the dysfunctions inherent in conventional money and banking and open the way to more harmonious and mutually beneficial trading relationships when done on a large enough scale that includes a sufficiently broad range of goods and services, spanning all levels of the supply chain from retail to wholesale, to manufacturing, to basic commodities, and labor services.

Balance Limits and Settlement

In mutual credit clearing there is a continual flow through each account. As described previously, account balances fluctuate up and down, being sometimes negative and sometimes positive. An account balance increases when a sale is made and decreases when a purchase is made. It is possible that some account balances may always be negative, which is not necessarily a problem so long as the account is actively trading, and the negative balance does not exceed some appropriate limit. What is a reasonable basis for deciding that limit? We needn’t stretch our imaginations too far in deciding about that. Just as banks use your income as a measure of your ability to repay a loan, it is reasonable to set maximum debit balances based on the amount of revenue flowing through an account—in other words, the maximum line of credit on any account should be decided mainly upon the basis of the amount of value that a member is able to provide to the circle, which is reflected in their volume of sales of goods and services into the circle. This should be averaged over some recent time period to smooth out seasonal and other normal business fluctuations. Past experience in conventional money and banking has provided a rule of thumb that may be useful here: a negative account balance should not exceed an amount equivalent to about three months’ average sales.[10]

Some have suggested that it is necessary that accounts be brought to zero periodically—i.e., that they periodically be “settled.” If there is an agreement to settle accounts periodically, that settlement would be presumably a cash settlement, although the transfer of other financial claims or assets could serve just as well. To settle accounts, those who have negative balances would put in enough cash to zero their account balances, while those with positive balances would draw out enough cash to also bring their account balances to zero. While periodic cash settlement might be used initially to build confidence in credit clearing as a viable alternative payment method, even that degree of dependence on conventional money is not a functional necessity and should eventually be phased out. As the credit clearing process becomes more familiar, people will come to realize that a properly managed clearing system can be relied upon to mediate their exchange transactions without the need for cash settlement.

Alternatively, accounts might be settled by the transfer of some privately or cooperatively issued local currencies, or some other financial claims like mutual fund shares or shares in real estate. But I consider settlement to be analogous to training wheels on a bicycle. Training wheels serve to provide initial support and to build confidence until the rider learns how to balance and control the bicycle. But at some point, it becomes clear that they are not needed—and, in fact, constitute an encumbrance to effective operation. So it is with settlement; clearing is a dynamic process in which only very minor adjustments are needed to maintain balance and stability. In a properly designed and managed credit clearing system, settlement may be dispensed with so long as credit lines are properly allocated and there is active trading through each account, and adequate provisions are made to prevent or cure defaults.

Providing Surety of Contract

At the same time, we should not be overly sanguine about people’s behavior where money and material wealth are concerned. The fundamental requirement in any payment system is to assure reciprocity. Reciprocal exchange means that a participant must, over time, put as much value into the economy (by making sales) as they take out of the economy (by making purchases). Gifts and charity should be provided for by other means apart from the clearing system in which reciprocal exchange is the fundamental purpose.

So long as there are competing exchange systems, including conventional banks and money, some provisions must be made to assure that participants in a credit clearing association do not drop out without first settling their balances. This can be achieved in a variety of ways. The most direct way is to require the pledge of some “collateral” or valuable assets as surety of contract, assets that would be forfeited in case of default. On this, we can take a hint from the Swiss WIR Business Circle Cooperative which was founded in 1934 in the midst of the Great Depression. Before it became a conventional bank in the mid-1990s, WIR was the largest and most successful mutual credit clearing system to date, providing credit clearing services to small- and medium-sized businesses throughout Switzerland. WIR required that account balances be secured, typically by the pledge of real estate (usually in the form of a second mortgage on the member’s home). It is important that the value of any such collateral should be used solely to assure that a member lives up to their agreement and should not be the basis for setting debit limits on an account. Those limits, as we have said, should be based on the amount of value an account is able to provide to the associated members of the group in the near term.

Another possible approach to allocating credit lines is “co-responsibility.” In this case, each member would join not as an individual but as part of an affinity group in which each member of the group shares the risks and responsibilities for defaults by any of its members. Such exposure would assure the development of solid “communities of interest” based on high trust levels and would require responsible participation in all relevant decisions, such as the admission to membership in the affinity group and the setting of debit limits on individual accounts. This might at first seem an onerous burden, but it is essentially what occurs in “group insurance,” in which each claim is paid for by the other members of the group by way of the “premiums” they pay periodically into a fund which is used for payouts as they are needed. This is also the case with conventional political currencies. Those of us who operate in the dollar economy, for example, are, whether we know it or not, co-responsible for satisfying all dollar claims held by others. The co-responsibility feature has been used effectively in the realm of micro-lending and has probably been a major factor in the success of the Grameen Bank and other microcredit systems that have been modeled after it.[11] Building a system of exchange and finance based on the foundation of high trust that already exists within groups of people who know each other will be far more solid and convivial than any centralized impersonal system could ever be.

An Insurance Fund

Despite the above measures, it is still possible that some small amounts of defaults may occur. Those losses to the association can eventually be covered by an insurance pool or “reserve for bad debts,” which is typical in any well-run business. The clearing system must have revenues sufficient to cover all of its operating costs, including the cost of “bad debts.” As mentioned earlier, such revenues might most reasonably be derived on a “fee for services” basis, charging a small percentage fee on each transaction, according to the amount cleared; that should provide ample revenues to support a clearing system that is operating at even a modest scale.

To sum up, mutual credit clearing circles can reclaim the credit commons from monopoly control, enabling members to act independently of the banks in allocating their credit and conducting their business and trading among themselves without being limited by the availability of political debt-money. The computing and communications technologies that are available today make the process of direct credit clearing between buyers and sellers entirely feasible and, at the appropriate scale, extremely economical. Such systems can with relative ease be implemented at all levels of the economy, from the local to the global. There are already available numerous software platforms that provide the required functionality for operating such networks. The main obstacles likely to be encountered are political ones, as vested interests try to maintain their monopoly privilege and prevent the emergence of competing systems of exchange. It therefore behooves us to act quickly in the establishment and proliferation of alternative exchange mechanisms so that they will achieve widespread patronage and support sufficient to resist political interference.

[1] Brittanica Money. https://www.britannica.com/money/clearinghouse. Accessed July 17, 2024.

[2] Market courts and lex mercatoria in late medieval England, in Medieval Merchants and Money: Essays in Honour of James L. Bolton, pp. 288-289. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv5132xh.20. Accessed July 20, 2024.

[3] Hugo Bilgram and L. E. Levy, The Cause of Business Depressions. p. 99. This entire book in PDF format is available at https://beyondmoney.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/the-cause-of-business-depressions.pdf.

[4] Ibid., p. 417.

[5] Thomas H. Greco, Jr. Money: Understanding and Creating Alternatives to Legal Tender. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2001, pp. 74-75.

[6] An Early Proposal for a Credit Clearance System: An excerpt from Bilgram and Levy, with prefatory comments by Thomas H. Greco, Jr. https://beyondmoney.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/an-early-proposal-thg-with-bl-transcript.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2024.

[7] Ibid.

[8] See my article Reconnecting the Monetary Economy to the Real Economy, at https://beyondmoney.net/2022/06/23/reconnecting-the-monetary-economy-to-the-real-economy/

[9] E. C. Riegel, Private Enterprise Money, p. 136.

[10] In banking terms, this is referred to as the “reflux” rate, which is the rate at which a currency is redeemed by an issuer. The rule of thumb from experience says that there should be a minimum daily reflux of one percent of the amount of currency issued, which means that the entire issue could be redeemed within a period of one hundred days, or roughly three months.

[11] This mention should not be taken as an endorsement of any particular microcredit program. There are other aspects of microcredit, as it has developed thus far, that have had negative consequences.

terrific, Thomas! This is exactly what we need, imo, out of the box thinking to build a globalist-free society. I'm going to feature it in my next substack.