Because meaningful, lasting change requires trust, we need place-based ecosystems that build community connections, expand on existing assets, and reward mutual support.

—Jenny Kassan

Throughout the world today, local communities are struggling to maintain their economic vitality and quality of life. The reasons for this are both economic and political and are largely the result of external forces that are driven by outside agencies like central governments, central banks, and large transnational corporations. In brief, decisions made by others outside of the community are having enormous impacts on life within the community. Yet communities can still reclaim significant control over their own welfare. They can ameliorate the effects of external forces by employing peaceful approaches that encourage human solidarity and are based on private, voluntary initiative and creativity.

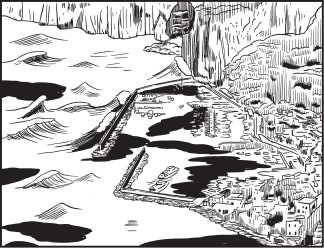

I often use the analogy of the small boat harbor, depicted in Figure 16.1, to convey the general idea of how local communities can protect their small enterprises while remaining open to the global economy. The process of globalization, while having many positive aspects, has been carried out in such a way and to such an extent as to be destructive to small businesses, local economies, and democratic governance. It is as if there were a deliberate policy to remove the sea walls from every small boat harbor in the world with the effect of exposing small boats to the turbulence of the open sea. As I put it in my lecture presentations, a rising tide may lift all boats, but the tidal wave of globalization smashes all but the biggest.

But just as the health of your body requires healthy cells and organs, a healthy global economy and a peaceful world require healthy local communities. Is there still a place for small businesses? Must every advantage be given to the corporate megaliths at the expense of small enterprises? The ancient economic debate that poses “free trade” against “protection” is too simplistic and fails to recognize that healthy economies require both free trade and protection, each confined within its proper limits. Communities need to create the equivalent of seawalls to protect their small enterprises and workers, while at the same time remaining open to the national and world economies.

It is encouraging to note the widespread awakening to the global multi-crisis and the plethora of creative responses to it. Sustainability, relocalization, decentralization, subsidiarity, human scale, appropriate technology, and the devolution of power are the current buzz. The big question, of course, is how can these be achieved in the face of the tremendous political, economic, and financial forces that are driving the increasing centralization of power and concentration of wealth?

The Orthodox Approach to Community Economic Development

Sadly, the orthodox approach to community economic development over the past several decades has centered upon efforts by state and local governments to recruit large corporations to come and set up operations in their area with the expectation that they will provide additional jobs for local workers, stimulate business for peripheral industries and the service sector, and ultimately add to local tax revenues. The consequent competition among cities and states in pursuing that strategy has resulted in corporations forcing enormous concessions from host communities in such forms as tax abatements and infrastructure provided at taxpayer expense. But capital is notoriously fickle, and government policies and international “free trade" agreements have given it unprecedented mobility. Quite often the experience has been for companies to leave town as soon as the “free lunch” has expired, only to play the same game again somewhere else. Michael Shuman, in his Main Street Journal article, Don't Put Lipstick on Corporate Pigs[1], states that:

“Study after study[2] has shown that efforts by cities to “attract and retain” nonlocal corporations through subsidies are completely counterproductive. Among the reasons:

Companies that receive these subsidies consistently underdeliver their promises, and many split town after the gifts run out.

The jobs created frequently pay miserable wages, and about 90% are taken by outsiders who move into the communities. This, in turn, requires infrastructure investments (roads, schools, water systems, etc.) that are never tallied as costs.

The structure of the incentives industry puts cities at a terrible disadvantage. Agents represent companies looking for their Payday, not cities looking for economic development.

The secrecy around these deals makes public accountability almost impossible, and makes public corruption among participating officials, who are greasing the wheel in the shadows, almost inevitable.

In comparison to large corporations, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) contribute proportionately more to the economy in jobs, productivity, and innovation. The OECD acknowledges that:

“SMEs are key players in national economies around the world. Representing 99% of all businesses, generating about 60% of employment and between 50% and 60% of value added in the OECD area, they can play a major role in delivering growth that is more inclusive and whose benefits are shared more broadly.[3]

And even the World Bank concurs, saying that:

“Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) play a major role in most economies, particularly in developing countries. SMEs account for the majority of businesses worldwide and are important contributors to job creation and global economic development. They represent about 90% of businesses and more than 50% of employment worldwide. Formal SMEs contribute up to 40% of national income (GDP) in emerging economies. These numbers are significantly higher when informal SMEs are included. According to our estimates, 600 million jobs will be needed by 2030 to absorb the growing global workforce, which makes SME development a high priority for many governments around the world. In emerging markets, most formal jobs are generated by SMEs, which create 7 out of 10 jobs. However, access to finance is a key constraint to SME growth, it is the second most cited obstacle facing SMEs to grow their businesses in emerging markets and developing countries. SMEs are less likely to be able to obtain bank loans than large firms; instead, they rely on internal funds, or cash from friends and family to launch and initially run their enterprises.”[4]

That being the case, doesn’t it make more sense to nurture the businesses that are already part of the local economy, companies that are locally owned and managed, and to foster the emergence of new ones? Like the Sardex trade exchange we described in Chapter 15, the owners of these businesses have a stake in the prosperity and quality of life in their home communities and are inclined to support one another in addressing common challenges. Communities that offer a high quality of life, an able workforce, and a clean and pleasant environment do not need to offer “bribes” to outsiders. But relocalization efforts cannot get very far without the creation of metasystems that support buying locally, selling locally, saving locally, investing locally, and most importantly, something that has been generally missing from local development initiatives—the local creation and allocation of credit to provide independent means of payment that circulate in parallel with government fiat currencies, such as the private and community currencies and credit clearing mechanisms we have been describing and prescribing throughout this book.

Conventional political forms of money, and huge banking companies which are owned and managed by remote entities, by their very nature militate against relocalization. Local actions need not be antagonistic toward those entities which can be made less relevant and less destructive by implementing creative methods that localize control over both finance credit and exchange credit.

A Comprehensive Community Economic Development Plan

As I see it, an effective strategy for local self-reliance, autonomy, and community empowerment must include ways to:

Keep money circulating longer within the local economy. (Buy Local)

Increase trading among local businesses in preference to outside sources and encourage new home-grown ventures to provide goods and services that are presently acquired from outside. (Import Substitution)

Enable the application of local capital to be invested in local businesses. (Invest Locally)

Provide credit and exchange media, like local currencies and direct credit clearing, that are independent of the banking system and federal government. (Independent Moneyless Exchange)

The Hague Academy for Local Governance outlines five steps for local economic development (LED)[5]:

Identify and Convene LED Stakeholders

Conduct a Local Economy Mapping and Analysis

Formulate your LED Strategy

LED Strategy Implementation

Progress Monitoring and Impact Assessment

Stage I: Map the Local Actors and Assets & Promote Import Substitution

Jane Jacobs has argued that cities, not nation states, are the salient economic entities, and that city and regional economies develop through a process of import substitution.[6] That being the case, it would seem reasonable that a regional economic development program should begin with actions that support that process.

The first stage of a local development program might look rather conventional and similar to the “buy-local” initiatives that have sprung up in many places, but it needs to be more comprehensive in its social, economic, and political aspects. It begins by organizing solidarity groups that include all sectors of the constituent communities, particularly the locally owned and controlled businesses, municipal governments, the nonprofit sector, social entrepreneurs, and activists. By building bridges between these groups and identifying common objectives, it should be possible to achieve the commitment to do the hard work necessary to move together toward greater regional economic self-sufficiency.

The first major task is to launch a “buy-local” campaign in which the economic resources and business relationships within the region are clearly mapped. That database can then be used to assist businesses in finding local sources for the things they buy and local customers for the things they sell. The services of brokers can be employed to help match available supplies with local wants and needs. Critical gaps are identified, and local entrepreneurs can be encouraged to find ways to fill them, perhaps with support from a local microlending agency or the many local investment funds that have been springing up in communities around the nation. As this process proceeds, the community becomes less dependent upon outside entities and more resilient and self-determining.

These measures alone, however, are far from sufficient. Given the fact that conventional money and banking are themselves externally controlled and act in ways that are parasitic upon local economies, some way must be found to reclaim at least a portion of the “credit commons” and bring it under local control. So, unlike conventional buy-local initiatives, this project moves quickly to implement the second stage.

Stage II: Support Structures for Localization—Saving, Investment, Finance, and Education

While the most fundamental need is for mechanisms that enable local control over the exchange function, the health and independence of local economies also requires the localization of savings and investments. In today’s world, locally owned and managed banks have become increasingly rare, most having been acquired or replaced by branches of huge bank holding companies that are owned and controlled by entities outside the region. Local savings deposited in those banks can, and do, get invested anywhere in the world, often in ways that are detrimental to the interests of the savers and the health of their local economies. They typically leave homegrown enterprises starved for capital while funding mega-corporations, weapons, war, and projects that are socially or environmentally destructive. Structures already exist, or can be created, to channel both savings and community-issued credits into enterprises that enhance local production and local quality of life.

“Buy local” initiatives have been common in communities around the world for long time, but that is only the beginning of community economic development. Providing both working capital and investment capital to local businesses and startups begins to get to the heart of what is needed. Many entities have sprung up in recent years to assume the role of providing investment capital, mostly in the form of loans and grants that are funded by both government entities and private non-profit. That is helpful as far as it goes but local business expansion also requires equity investments which represent shared ownership that carries no burdensome interest costs or repayment schedules. But up until recently sources of equity finance were limited to accredited investors,[7] typically venture capital funds and angel investors which have demanded large shares of the business and/or significant measures of control. What has been missing is the opportunity for small, non-accredited investors to put their savings into local SMEs.

But, since The JOBS (Jumpstart Our Business Startups) Act was signed into law on April 5, 2012, it has become easier for small businesses and startups to raise capital, especially by easing securities regulations and opening the door to equity crowdfunding for even non-accredited investors. The regulations allow those with modest income to invest a few thousand dollars annually, while higher earners may invest up to 10% of their income or net worth.[8]

Fortunately, the past several years have seen the emergence of a great many sources of sound guidance in the area of community economic development; these include Michael Shuman’s Main Street Journal,[9] Common Future,[10] National Coalition for Community Capital,[11] and Crowdfunding Ecosystem,[12] to name just a few.

Stage III: New Liquidity Through Trust—Mutual Credit as a Way to Pay

Even the most promising local businesses can struggle—not from a lack of customers, but from a shortage of cash flow. Traditional loans are often out of reach or come with high interest rates and rigid terms. Even crowdfunding does not typically address the liquidity problem in that it provides only conventional fiat money for capital improvements, not an alternative form of payment. But mutual credit clearing offers an elegant solution grounded in trust and reciprocity.

As we’ve already laid out in previous chapters, particularly Chapter 11, mutual credit clearing enables a new paradigm in economic relationships. It is a system where businesses extend interest-free credit to one another, settling trade obligations without needing conventional money. Think of it as a smarter, more adaptive form of multilateral barter—anchored not in cash, but in trust and productive capacity.

How It Works

Each participating business is granted a credit line or “overdraft privilege” based on its capacity and reliability.

Transactions are recorded as debits and credits in a shared ledger.

A business can buy goods or services today and repay (reciprocate ) later by selling its own goods into the network.

Key Benefits

Homegrown Liquidity: No need to rely on banks—credit is created by the network itself.

Zero Interest: Businesses avoid interest burdens and predatory debt cycles.

Increased Local Trade: Members are incentivized to buy and sell within the network, deepening regional ties.

Shock Resilience: The system softens the impact of inflation, bank failures, or policy shifts.

Trust-Based Cooperation: Participants grow closer as they share economic responsibility.

Dynamic Credit Limits: Credit capacity grows with trade volume, rewarding active participants.

The result is a system of trust-powered liquidity that reduces dependency on banks and expands local trade, by empowering local communities to create their own purchasing power.

The Generation and Allocation of Trade Credits

This topic was well covered in the final sections of Chapter 11, but we will summarize it here. The allocation of credit within a clearing exchange involves the granting of an “overdraft privilege,” which means that a member’s account may have a negative balance up to some specified limit. In allocating lines of credit, it is important, especially in the beginning, to allocate the greatest share of credit to “trusted issuers” which are well established, financially sound, and whose products and services are in greatest demand within the local region. This is the key to maintaining a rapid circulation of credits through the system, avoiding defaults, and preventing the excessive accumulation of credits in the hands of businesses that cannot easily spend them. In brief, the businesses that you wish to have accept community credits in payment are the ones that should be issuing them in the first place. By beginning with “trusted issuers” the value and usefulness of the community credits is quickly demonstrated beyond any doubt. As the process gains credibility and general acceptance in the community, more businesses and individuals will want to join the credit clearing exchange, and as each member develops a trading history, they too can qualify for an overdraft privilege commensurate with their volume of sales within the system.

Like any network, a credit clearing system becomes more valuable and useful as it continues to expand and a greater variety of goods and services become available within the network. By way of example, one may note that the first fax machine was very expensive—but useless until there were more fax machines for it to communicate with. As more fax machines were deployed and connected in an expanding network, the fax became more valuable to all users, even as prices plummeted and quality improved. The same will happen with clearing networks, but it is essential that the network, and each node in it, be properly designed and operated from the very start.

Stage IV: The Credit of “Trusted Issuers” Can Provide a Local Alternative Currency for General Circulation

The fourth stage of the program is the joint issuance of credits into the general community by the members of the clearing association. This is accomplished when the association members begin to buy goods and services from non-members who are outside the credit clearing circle. They make these purchases by using some form of uniform credit instrument, like a voucher or certificate, which all association members are obliged to redeem, not for cash, but for the goods and services that are their normal stock in trade. Those vouchers provide a sound regional currency based on the productive capacity of the region’s leading enterprises, a currency that can circulate among any and all as a supplemental medium of exchange. The availability of such a currency to supplement the flow of official money insulates but does not isolate the local economy. Just as a seawall protects a small boat harbor from the turbulence of the open sea, a sound regional currency provides a measure of protection from the turbulence of the global economy and centralized banking and finance.

This externalization of credits from within the clearing circle into the general community can be achieved using any of several available forms and devices. Credit vouchers may take the form of paper notes, coupons, or certificates; they might be placed on stored value cards like the gift cards that are commonly issued by major retailers and are so popular these days with consumers; or they could manifest as credits in accounts that reside on a central server that can be accessed by use of a debit card and point-of-sale card reader.[13]

Stage V and Beyond: Transition to an Objective Measure of Value and Unit of Account

Eventually, it will become necessary to denominate local credits in some independent, objective, nonpolitical unit of account based on a concrete standard of value. This will become especially important as political currencies like the US Dollar continue to be debased, causing galloping inflation of market prices, and as local clearing networks become interlinked regionally and across national boundaries. Trade credit units originally defined as being equivalent to the dominant political currency unit (like dollars, pounds, euros, and yen) will shift over to a value unit like we’ve already described that is objectively defined in terms of valuable, commonly traded commodities. Such a unit will facilitate trading across national borders by obviating the need for foreign exchange and eliminating the exchange rate risk and will be immune to the inflationary or deflationary effects that beset national political currencies.

Together, the actions we have outlined above comprise an effective strategy for achieving economic sovereignty. All of the major system components are well-developed and readily available. With a modest amount of funding or investment, programs designed along these lines can be quickly launched and a credit clearing system can quickly reach critical mass. We can expect that success in one or two local regions will inspire others to emulate it, leading to a rapid proliferation of healthy and sustainable communities that can associate to form a worldwide economic democracy.

[1] https://mainstreetjournal.substack.com/p/dont-put-lipstick-on-corporate-pigs. Accessed June 9, 2025.

[2] https://reinventalbany.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Reinvent-Albany-Debunked-25-Studies-on-Corporate-Handouts-Spring-2023.pdf. Accessed June 9, 2025.

[3] Strengthening SMEs and Entrepreneurship for Productivity and Inclusive Growth. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/strengthening-smes-and-entrepreneurship-for-productivity-and-inclusive-growth_c19b6f97-en.html. Accessed May 28, 2025

[4] Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) Finance.https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance?form=MG0AV3&form=MG0AV3. Accessed

February 27, 2025,

[5] https://thehagueacademy.com/news/five-steps-to-designing-a-local-economic-development-strategy/. Accessed May 12, 2025

[6] Jabe Jacobs, Cities and the Wealth of Nations. New York: Vintage Books, 1985.

[7] In brief, an accredited investor is one who is required to have high income and net worth. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/accreditedinvestor.asp.

[8] https://www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/how-to-invest-in-a-small-business/

[9] mainstreetjournal.substack.com/

[10] https://commonfuture.co/

[11] https://www.nc3now.org/

[12] https://www.crowdfundingecosystem.com/

[13] For more on the issuance of an alternative currency, refer to Chapter 14, particularly the section, “Principle 2: On What Basis Should Currency Be Issued?” https://beyondmoney.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/eom-rev_ch14-final-.pdf